Arcadia Revisited. 2014. Oil on Board. 140x120cm

Drifting. 2014. Oil on Paper on Board. 39x39cm

From Above and Beyond. 2014. Oil on Canvas. 50x40cm

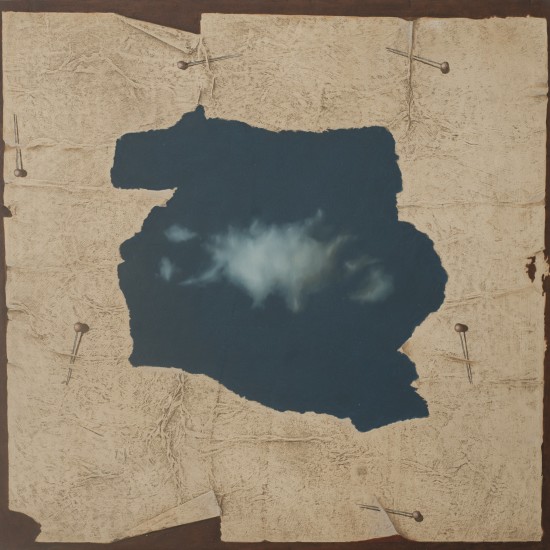

Map With Cloud. 2014. Oil on paper on Board. 41x39cm

Maps with Clouds. 2014. Oil on Paper on Canvas. 45x45cm

No Entrance. 2014. Oil on Paper on Board. 39x42cm

Out of Kilter. 2014. Oil on Board. 55x60cm

Still Waiting. 2014. Oil on Paper on Board. 39x39cm

Study for Arcadia Revisited. 2014. Oil on Paper on Board. 39x42cm

The Breach. 2014. Oil on Paper on Canvas. 45x61cm

The Edge of Reason. 2014. Oil on Board. 91x72cm

The Flag. 2014. Oil on Paper on Board. 39x39cm

The Lost Treasure. 2014. Oil on Canvas. 45x45cm

The Thin Skin. 2014. Oil on Paper on Board. 60x54cm

Watcher. 2014. Oil on Board. 19x22cm

Weatherstation. 2014. Oil on Board. 105x90cm

Wormhole. 2014. Oil on Paper on Board. 30x30cm

Landscape with Craters. 2015. Oil on Board. 60x60cm

Tangible Reminder. 2015. Oil on Board. 60x60cm

The Field with Young Leeks. 2015. Oil on Board. 42x39cm

Vents. 2015. Oil on Board. 60x60cm

As Far as the Eye can See

On a morning in November 2012 I woke up and listened to the news on the radio. One short news-item caught my attention: a small island, Sandy Island, which had been charted for centuries as being located in the South Pacific, turned out to be non-existent. Scientists from the University of Sydney went to the area, but found not an island, just 1400 metres of deep ocean. I jumped out of bed, checked Google Earth and printed off this supposedly satellite image of Sandy Island. Just in time, because later that same day Google deleted it from its maps.

Maps are the ultimate representation of land and place. Give me a map and I will be absorbed, and journey in my mind’s eye along its roads, pathways, and contours. I will follow its rivers and navigate its shorelines.

However, maps are also constructions. They are made as tools to survey, to exert control, to appropriate. A blank map instils fear, we need to give meaning, to be able to interpret. In these days, a time of surveillance and information, not a lot of places are left blank on the map for our imagination to roam free. We are the master controllers over our environment, over the place where we live, our planet, and all needs to be mapped as far as the eye can see. The unmapping of Sandy Island unexpectedly reversed that process. Only for a tiny moment, involving a really small place. Yet, it made my day that November.

It is a quite literal illustration of what George Perec writes about in his book “Species of Spaces and Other Pieces”: ‘I would like there to exist places that are stable, unmoving, intangible, untouched and almost untouchable, unchanging, deeprooted; places that might be points of reference, of departure, of origin. Such places don’t exist, and it’s because they don’t exist that space becomes a question, ceases to be self evident, ceases to be incorporated, ceases to be appropriated. Space is a doubt: I have constantly to mark it, to designate it. It’s never mine, never given to me, I have to conquer it.’ As someone who has left their country of origin, place is always a question mark.

Just like a map there is the image of a landscape as a representation of space, of place. My first painting of a landscape (years ago) depicts a Dutch landscape. The viewpoint is from the foreshore, literally from the sea bottom at low tide, looking at the sea dyke with the land lying behind, out of sight. In that sense it is a strange landscape, viewed from a place that only exists when the tide is out; transient and impermanent. The only solid body is the dyke, but then, being born below sea level, the question always is: how strong is that dyke really?

If the identification of a place depends on a name, a solidity, then, in a sense, the bottom of the sea is a non-place, an ‘ou-topos’ (utopia). And more and more the landscapes and maps in my images distance themselves from real, objective places, although elements of those are always present.

They are places that are torn up, surveyed, abandoned, fragile in existence.

They are places without names or solid foundation.

They are places with a stark horizon, the gap between heaven and earth, the gap where the unexpected can happen.

They are places as far as the eye can see….. But how far is far and how perceptive is the eye?

Exhibition

Category

Paintings